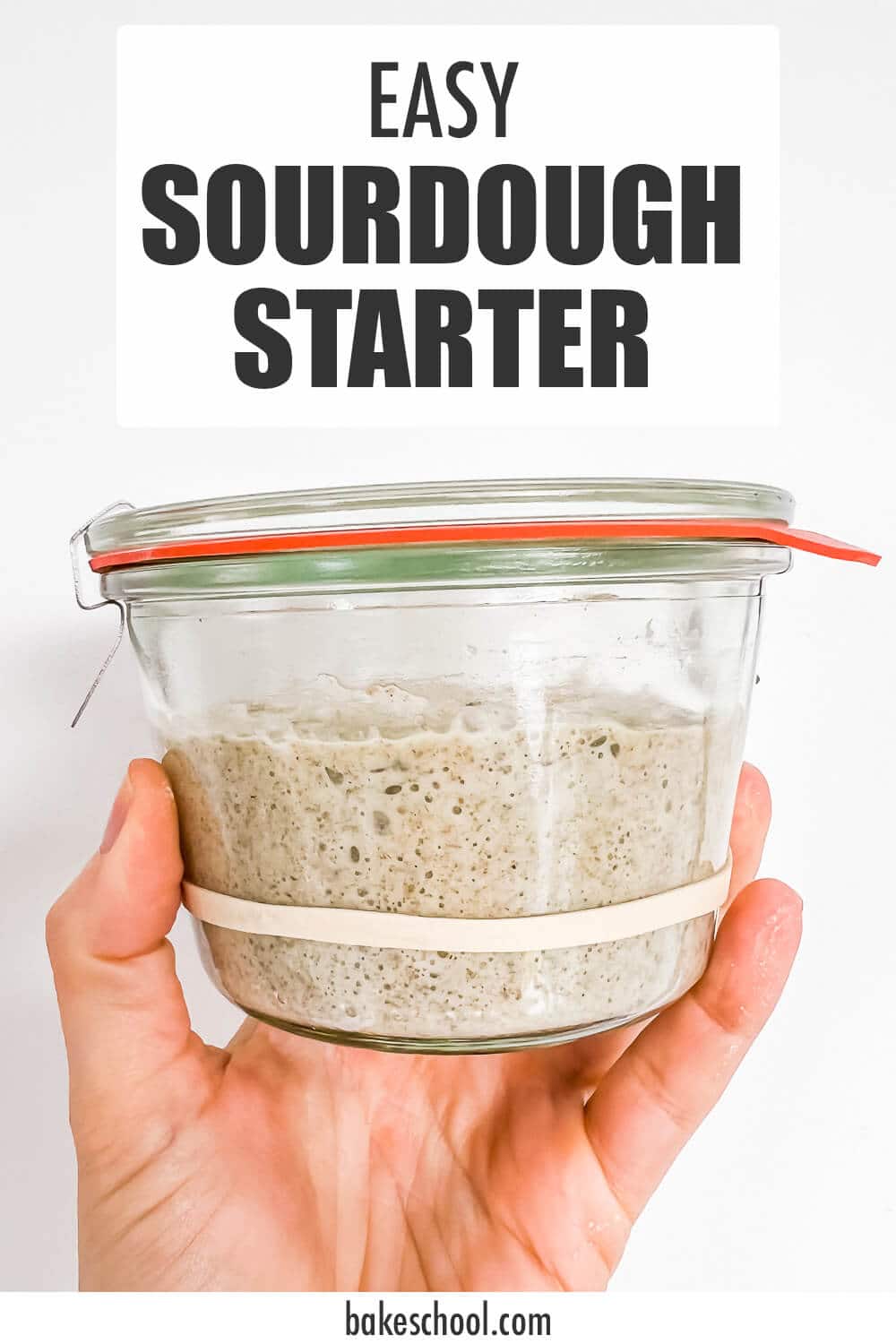

Learn how to make an active sourdough starter from flour and water with this easy recipe and step-by-step photos. You will also find out how to maintain and feed an active starter, including a feeding schedule and storage tips.

If you want to bake flavourful sourdough bread, you will need an active sourdough starter. You can get a sample of starter from a friend or your local bakery and that will make the process infinitely easier and faster. Or you can make your own.

It's a good idea to learn how to make a new starter in case your starter dies. You don't know how many times I've heard of somebody accidentally microwaving or baking their starter, killing it. Bookmark or save this post for later, just in case!

Jump to:

- The science of building a sourdough starter

- Ingredients

- Temperature is an important part of the equation

- Substitutions and variations

- Equipment

- First steps

- Feeding and maintaining

- Smell and visually inspect at every step

- Feeding schedule

- Storage

- Kahm yeast

- Tips for success

- 📖 Recipe

- FAQ

- What to do with all the discard

- Recommended baking books about sourdough bread

The science of building a sourdough starter

Sourdough starter is nothing but flour and water, mixed together and left to sit at room temperature to ferment. It might seem a little scary to let the mixture ferment like that. It probably feels counterintuitive and a breeding ground for microorganisms. It is!

In the beginning, all kinds of microorganisms (yeast and bacteria) will feed on the mixture you have created and they will grow, digesting the food you have provided. Over time, you will notice the scent of your starter evolves, becoming more sour: the starter is becoming more acidic. The pH of your starter will drop below 5 as it matures.

Lactic acid bacteria slowly overtake the culture and bring your starter into a food-safe zone. That is why a sour smell develops. It's the same principle as when you make yogurt at home! You start with pasteurized milk that has a pH above 6. You warm the milk and inoculate it with microorganisms (lactobacillus) that will start to break down the lactose and sugars in the milk. As the sugars break down, the pH of the milk lowers to around 4.

The lactic acid bacteria create such an acidic environment that the "bad" microorganisms that we shouldn't consume will die off. They don't survive in acidic conditions. They aren't built for it. The lactic acid bacteria create an environment that is perfect for making yogurt or sourdough bread that is safe to consume.

The acidic environment of the starter is also perfect for growing certain types of yeast, like Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These yeast cells consume sugar, digesting it down to carbon dioxide gas, which helps your bread rise.

The acidity is what makes sourdough starter safe, creating the perfect environment for yeast to thrive so that you can use it as a leavening agent. That's why it's important to keep those lactic acid bacteria happy, feeding water and flour regularly!

Ingredients

The number of ingredients you need to make a sourdough starter from scratch is even less than what you need to make sourdough bread! You really only need two ingredients. Three if you'd like to use a combination of two flours.

- Flour—I use a mixture of bleached all-purpose flour and rye flour to build and maintain my sourdough starter, but you can stick to just all-purpose if you prefer (more on that later).

- Water—regular tap water is fine and that's what I use.

See the recipe card for quantities.

Your starter is alive. As you continue to feed it daily (or weekly), you are basically training it. Consistently feeding it at the same time of day with the same ingredients is key for it to thrive. If you change a variable, you may throw it off balance.

Temperature is an important part of the equation

Temperature is as important as the flour and the water that goes into building a new starter. Starter cultures thrive in a warm, but not too warm environment. Warm living conditions are key to starter activity:

- An environment that is cool will slow down your starter and they will be more sluggish, growing at a slower rate

- An environment that is too hot will lead to overfermentation and you will likely kill the microorganisms if the temperature gets out of hand.

You might be wondering what is too hot and what is too cold, and what temperature is just right for creating and maintaining an active sourdough culture:

- Too hot: Don't let your starter get much warmer than 28 °C (83 °F) because the culture will be too active initially and die off more quickly if you don't feed it enough and often

- Too cold: Below 4 °C (when water begins to freeze), your starter will slow down completely and stop growing. This is why you can store a sourdough culture in the freezer for longer-term storage.

Ideally, you would ferment and proof a wheat-based dough somewhere between 24 and 26 °C (75 and 78 °F). At this temperature, the culture will be active, but steady.

Depending on the time of year and the season, it may be hard for you to control the ambient temperature of your kitchen. For this reason, bread bakers will play with the temperature of the water they use to feed their starter and make bread in order to make adjustments to the temperature of the dough.

- If your kitchen is warmer than the optimal fermentation temperature (over 26 °C or 78 °F), consider using cooler water (around 21 °C or 70 °F)

- If your kitchen is colder than the optimal fermentation temperature (below 24 °C or 75 °F), consider using warmer water (27 to 30 °C or 80 to 85 °F)

This way you can keep the microorganisms happy and thriving, ensuring your starter and bread will ferment in a timely fashion (not too fast, and not too slow)!

Substitutions and variations

With only two ingredients, there's not much wiggle room. Still here are some options

- Flour - use any flour to feed your starter, even bleached all-purpose. I use a combination of bleached all-purpose and rye flours. The microorganisms like the whole grain flours and your starter will likely grow faster if you incorporate a little whole grain flour into each feed.

- Water - tap water generally is fine

- Sugar - there's no sugar in this recipe, per say, but there is flour. Flour is made up of carbohydrates, specifically long chains of sugars. You don't need to add sucrose (granulated sugar) to feed your starter because the microorganisms will digest the carbohydrates in flour to feed themselves. However, some bakers may add a tiny amount of honey or sugar in colder months and/or wintertime, when the starter may be slower and more sluggish. The sugar is a simpler form of feed for the microorganisms to digest and so gives them a quick boost of energy!

If you bake gluten-free, you can make a starter from gluten-free flour instead!

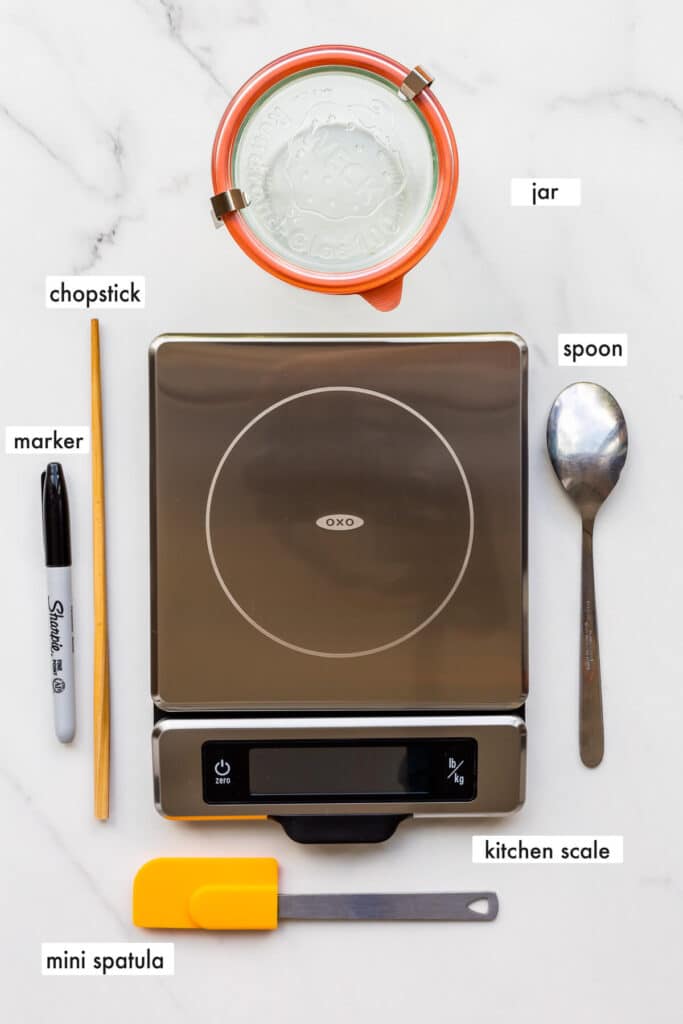

Equipment

You don't need much to build a starter. Some people will literally mix the ingredients in a bowl and may even use a plate as a cover. I like to use jar with a lid, personally. A glass jar comes with a risk: it's breakable! If you break your jar with your starter inside, you will have to throw everything out and start over.

For this reason, some favour clear plastic containers with lids to hold their starter. Since you will be discarding and feeding daily, there's no risk of breaking the container if it's plastic.

Check out my sourdough baking list on Amazon US and Amazon Canada for more equipment suggestions.

First steps

Building up and maintaining a sourdough culture is very repetitive. You will be doing most of these steps daily at the beginning, and then twice daily even, storing it at room temperature. Once the starter is healthy and established, you will likely switch to feeding it once a week, storing it in the fridge to slow down growth.

Before you begin, you will need an empty jar, preferably one that has a wide opening. You should record the weight of the empty jar (without the lid) on a kitchen scale on the bottom of the jar so that you can easily subtract the jar weight and know exactly how much starter is in your jar at any time.

Building a new sourdough starter is easy. All you have to do is mix together flour and water in your jar!

Combine the water and flour in a jar that is at least 375 mL (1-½ cups). Mix it well and scrape down the sides to keep the walls as clean as possible.

Close the lid and mark the height of the starter with an elastic band or a permanent marker. Store it in a warm, dry place for up to 2 days.

Discard two-thirds of the starter.

Feed the remainder: replace the lost weight with equal parts of water and flour, by weight.

You will repeat the process of discarding and feeding over and over again until you notice your starter rises and falls on a regular schedule. It will usually take about 6 to 12 hours for it to double (more or less depending on type of flour used, maturity of starter, and temperature).

Hint: do not forget to feed your starter! If you are keeping your starter at room temperature, you have to feed it daily, if not twice daily, to maintain the microorganisms responsible for keeping the starter at a safe pH below 5. Store your starter in the fridge during busy periods to slow it down. This way, you only have to feed it once every week.

Feeding and maintaining

Once you've mixed your first starter, you have to feed it on a regular schedule. How often you feed your starter will depend on many variables:

- how mature it is—the more alive and active the culture, the more often it will need to be fed

- the ambient conditions in your house and even the season—even in a fairly climate-controlled environment that is maintained at around 22–23 °C, your starter will behave differently in winter than it does in summer. In summer, your starter will be more active and demanding than it is in winter

- how much you fed it the last time—if you fed your starter just a little, you will need to feed the starter again within a few hours (like if you fed it water and flour at half of the weight of starter)

- how much starter you have left after discarding a portion—the less you carry over, the higher the proportion of food compared to starter, the longer it will take to grow and multiply.

So how do you know when to feed it? When you see that the starter has risen and begun to fall, it's time to feed it again. You can tell it's falling by looking at the sides of the jar: you will see a thin line of residual starter at the level it peaked, and you will see thin streaks trailing down to the level it's currently at.

In the beginning, you may feed it only once a day because it will be slow and underdeveloped, but as the starter matures, you will have to feed it twice at room temperature.

Smell and visually inspect at every step

I highly encourage you to smell your starter before and after every feeding from the day you first mix flour and water. Take notes each time. You will notice the odours of the starter will evolve.

When you first mix your first starter, it won't smell like much of anything. Maybe a little sweet when you first mix flour and water. Nothing special. After a day or two, the smell will start to change.

When you first mix your starter, or when you feed it, it will be a fairly thick, dense paste. A day after feeding, your starter will be thinner, more fluid, and very bubbly from the gases the microorganisms release.

First to third feeding

After you've let it sit for a day or two, you will notice a distinctly cheesy scent when you open the jar to discard and feed it. It will be quite pungent and rather shocking. After you feed it, the scent will have mellowed a little.

At the second and third feedings, you will likely still smell mostly cheesy scents from your starter.

Fourth feeding

This is where I notice a change in the smell of the starter. The cheese smell is still there when you stir it, but the initial scent when you open the jar will be a little sour or vinegary. That's the lactic acid bacteria working their magic!

Fifth feeding

Your starter will likely smell quite vinegary/acidic. You should start feeding it multiple times a day at this point to make sure the microorganisms aren't too hungry. If they get too hungry, the lactic acid bacteria will release a lot of acetic acid, as opposed to lactic acid. Your starter activity will dwindle as more acid is released.

Sixth feeding and beyond

The scent of the starter will evolve over time, and you might notice a faint odour of alcohol at some point. That's normal. Pay close attention to the smell before and after every feeding. The smell is a good indication of the health of your starter and the smell will tell you if something is wrong.

You should also visually inspect your starter often. Check for signs of discolouration or unusual patches (which could be a sign that your starter isn't acidic enough anymore and that mold is present).

Feeding schedule

These are guidelines to get you started but make sure to keep an eye on your starter, especially at the beginning, to feed the starter after peaking when it begins to fall.

- First week, feed daily, storing the starter at room temperature between feedings

- Second week, feed twice daily, storing the starter at room temperature between feedings

- Third week (or when the starter is rising and falling every 8 hours), feed weekly and store the starter in the refrigerator.

Storage

Once my starter is well established, smelling like a mixture of alcohol and vinegar, and rising and falling regularly, I store it in the refrigerator between feedings. I recommend you do the same because otherwise you may feel like you are having to babysit it too much.

It takes two to three weeks for me to build a healthy starter from scratch. The timeframe will vary greatly (with temperature, with the feeding schedule, ingredients, conditions, etc.). It could take a whole month to get your starter active and stable. It likely won't take less than 2 weeks though.

When it's time to bake, I take out a portion of the refrigerated starter the night before I want to make sourdough:

- I feed the portion as usual and let it rise at room temperature until it's peaked and ready to bake with (usually 7—12 hours later at around 21–24 °C).

- I feed the remaining starter that is in the fridge, replacing what I took away with equal parts flour and water by weight.

Longer term storage

If you are going to be away for an extended period or too busy to feed your starter once a week, consider freezing a portion of it or even drying some of it out in a dehydrator or a low-temperature oven. It will even dry out if you spread the starter thin on parchment paper and leave it on the counter at room temperature for a few days.

With a dehydrated starter, understand that when it's time to revive your starter, you will likely have to build it back up quite a bit, feeding it three or four times over the course of a week to bring it back to life. Still, this is likely easier than starting over.

I've read that many bakers have left a starter unfed in the refrigerator for a full year and still managed to revive and bake with it after just a couple of feedings. So it is possible.

Long-term refrigerator storage will likely cause your starter to give off a lot of alcohol, which may look like a dark clear liquid floating above your starter. Some bakers pour off the liquid before feeding, others just stir it in and then feed it. Sourdough bakers refer to the liquid as "the hooch" because it's alcohol, likely ethanol, as well as acids and water.

In all cases, if you see signs of mold or if your starter looks suspicious (change in colour or off odours), proceed with extreme caution if you are unsure. I recommend throwing out a starter that's gone moldy and starting over. Better safe than sorry.

Kahm yeast

A type of yeast called Kahm yeast may grow on a neglected starter. It will appear on the surface and look powdery and white. Kahm yeast sometimes floats over the layer of alcohol that separates out of your starter if the time between feedings is much too long.

Kahm yeast isn't harmful. If your starter develops a layer of it, you can just scrape that layer off, transfer the remainder of your starter to a clean jar and feed it.

The problem with Kahm yeast is that if it gets out of control, it can quickly take over the sourdough culture. The pH of your starter may increase, especially if there's more Kahm yeast than lactic acid bacteria. As the pH of your starter rises up, the starter will have a pH out of the "safe zone" and other microorganisms may grow. Your starter is at risk.

It's important to gain back control if you experience a Kahm yeast outbreak and make sure the pH comes back down below 5. Otherwise, your starter may develop mold and you likely will have to toss it out.

Tips for success

Work clean! Whenever you open the jar to discard and/or feed your starter, always use clean tools. You don't want to introduce any contaminants beyond what is coming from the flour and the water.

Remember that your starter is a culture of microorganisms. It's alive! You will have to nurture it to keep it happy and alive. Treat it like a member of your family by feeding it flour and water regularly.

If you don't have time for regular feedings, consider storing your established starter in the fridge, and even explore other options like drying or freezing portions of the starter to ensure you always have a backup stash.

📖 Recipe

Sourdough Starter

Equipment

Ingredients

- 50 grams water

- 50 grams bleached all-purpose flour or a mix of half all-purpose and half rye flour

Instructions

- Weigh your empty, clean jar (without the lid). Write the weight on the bottom of the jar.

Mix your starter

- Place the flour and water in the empty jar. Stir them together with a chopstick or a small spatula until the mixture forms a smooth paste. Smooth and level the paste so it's flat in the jar.

- Place the lid on the jar (don't tighten it too much).

- Stretch an elastic and slide it around the jar to mark the level of the starter.

- Set the jar in a warm, dry place, away from the light for 1–2 days. Keep an eye on it. It will likely more than double and fill up the jar almost to the top.

First feeding

- Open your risen jar of starter and smell it. It will likely smell like funky cheese.

- Place the jar on your scale and zero it.

- Stir the starter with a spoon, then remove 80 grams and throw it out.

- Add 40 grams of water, stirring it in with a chopstick or a small spatula, then add 40 grams of flour. Stir to form a thick paste.

- Close the jar. Verify that the level of the starter is still at the level of the elastic band.

- Set the jar in a warm, dry place, away from the light for 1 day. Keep an eye on it. It will likely more than double and fill up the jar almost to the top.

Second feeding

- Open your risen jar of starter and smell it. It will likely still smell cheesy.

- Place the jar on your scale and zero it.

- Stir the starter with a spoon, then remove 80 grams and throw it out.

- Add 40 grams of water, stirring it in with a chopstick or a small spatula, then add 40 grams of flour. Stir to form a thick paste.

- Close the jar. Verify that the level of the starter is still at the level of the elastic band.

- Set the jar in a warm, dry place, away from the light for 1 day. Keep an eye on it. It will likely more than double and fill up the jar almost to the top.

Third feeding

- Open your risen jar of starter and smell it. It will likely still smell cheesy.

- Place the jar on your scale and zero it.

- Stir the starter with a spoon, then remove 80 grams and throw it out.

- Add 40 grams of water, stirring it in with a chopstick or a small spatula, then add 40 grams of flour. Stir to form a thick paste.

- Close the jar. Verify that the level of the starter is still at the level of the elastic band.

- Set the jar in a warm, dry place, away from the light for 1 day. Keep an eye on it. It will likely more than double and fill up the jar almost to the top.

Fourth feeding

- Open your risen jar of starter and smell it. It will likely smell cheesy with a hint of vinegar.

- Place the jar on your scale and zero it.

- Stir the starter with a spoon, then remove 80 grams and throw it out.

- Add 40 grams of water, stirring it in with a chopstick or a small spatula, then add 40 grams of flour. Stir to form a thick paste.

- Close the jar. Verify that the level of the starter is still at the level of the elastic band.

- Set the jar in a warm, dry place, away from the light for 1 day. Keep an eye on it. It will likely more than double and fill up the jar almost to the top.

Fifth feeding

- Open your risen jar of starter and smell it. It will likely smell quite vinegary now.

- Place the jar on your scale and zero it.

- Stir the starter with a spoon, then remove 80 grams and throw it out.

- Add 40 grams of water, stirring it in with a chopstick or a small spatula, then add 40 grams of flour. Stir to form a thick paste.

- Close the jar. Verify that the level of the starter is still at the level of the elastic band.

- Set the jar in a warm, dry place, away from the light for 1 day. Keep an eye on it. It will likely more than double and fill up the jar almost to the top.

Sixth feeding

- Open your risen jar of starter and smell it. It will likely smell very vinegary and be very bubbly, with signs that it has risen and fallen slightly.

- Place the jar on your scale and zero it.

- Stir the starter with a spoon, then remove 80 grams and throw it out.

- Add 40 grams of water, stirring it in with a chopstick or a small spatula, then add 40 grams of flour. Stir to form a thick paste.

- Close the jar. Verify that the level of the starter is still at the level of the elastic band.

- Set the jar in a warm, dry place, away from the light for 1 day. Keep an eye on it. It will likely more than double and fill up the jar almost to the top.

Notes

FAQ

Remember that microorganisms are everywhere. They are in the water, hiding in bags of flour, on your body, and even in the air. When you hydrate the flour, you have basically created a tasty environment for these microorganisms to feed and grow. As the lactobacillus begin to replicate in your starter, they will expel lactic acid, lowering the pH, and killing certain microorganisms. Only certain types of yeast and bacteria can survive in this environment.

You actually don't have to discard every time you feed your starter, but discarding and feeding is also a good way of refreshing your culture, to make sure that the jar is filled with more active than inactive microorganisms.

You should remove a portion of starter and replace it every time you want to feed your starter, but you don't technically discard it. Remember to discard is to throw out. You can store your discard in a separate jar in the refrigerator and use your discard to make crackers, pancakes, crêpes, or even banana bread.

The elastic is placed to mark the height of the starter when you first feed it. This way you can see the starter grow and expand and know it’s active and breathing. If you feed it and it doesn’t rise above the level of the elastic, the starter is likely too young, slow and unhappy, or possibly dead. An active starter will double within a few hours after feeding. If it rises and falls, you will notice streaks of starter on the sides and that shows that you need to feed your starter again to keep it happy and active.

You could also use a permanent marker or a piece of masking tape for this job to mark the height of the starter after feeding.

The amount you feed your starter is pretty arbitrary. It really doesn't matter as long as you are feeding regularly. A good rule of thumb is feed the exact weight of starter that you use or discard. So if you removed 50 grams of starter, replace it with 50 grams of flour and water (so 25 grams of each). You can feed higher amounts than this and I often do if I want to have enough starter to make sourdough crackers.

Some bread bakers swear by the float test: they spoon a dollop of starter into a tall glass of water. If the dollop floats, they say the starter is active and ready (because it's full of air and buoyant). I don't think this is reliable. I prefer to bake with a portion and see what happens.

What to do with all the discard

When you first mix a new a new starter, I suggest composting the discarded portions. They smell of pungent cheese and it's not very appetizing. I'm just not a fan of using the discard at this stage.

Once the culture smells like vinegar and is more acidic, at that point, I start a big jar of discard. Every time I discard a portion of starter, I add it to the jar of discard. That jar is stored in the fridge to slow down the microorganisms.

Once you have about a cup of discard (250 grams roughly), you can make sourdough discard crackers. It's the only thing I do with it. Sometimes I mix it with more flour and water to make crêpes, but that's rare. My go-to for using up discard is sourdough crackers.

Recommended baking books about sourdough bread

If you want to go more in-depth into the world of sourdough and bread baking, I recommend these books:

- Flour Power by Tara Jensen

- Tartine Bread by Chad Roberton

- Tartine number 3 by Chad Roberton

- Bread Book by Chad Robertson and Jennifer Latham

Leave a Reply